Patrick Barkham, Richard Godwin, Amelia Tait & Jamie Waters

2020 has been a difficult year, but there are some glints of light in the gloom. From nature-friendly farms to anti-ageing worms and even a way of conjuring vodka out of thin air, here are a few nuggets of good cheer to look forward to in 2021

‘2020 has forced a recalibration of ambitions and expectations on a personal level’: Professor Peter Frankopan says this year will, largely, be good for us. Photograph: Jan Von Holleben/Trunk Archive

A vaccine for HIV: ‘This is an incredibly exciting result’

The Covid-19 vaccinations captured the world’s attention in November yet, around the same time, researchers behind a trial known as HPTN 084 also published spectacular results. The trial, which took place across seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa, found that an eight-weekly injection with a drug called cabotegravir was more effective than daily medication in an oral pill form in preventing HIV in women.

An estimated 38 million people in the world are currently living with HIV – two thirds of these people live in Africa. In South Africa, more than 62% of the 7.5 million adults living with HIV are women. While a pre-exposure prophylactic pill is currently available for people at risk, the HPTN 084 trial – undertaken by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) and partly funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – found cabotegravir to be 89% more effective.

“The injection overcame many of the challenges that women in the region experience with taking a daily pill,” trial chair Dr Sinéad Delany-Moretlwe says, explaining that stigma often prevents people taking their pill consistently. “Partners may feel insecure because they think it means their partners are going to be unfaithful and just generally women experience judgments about being sexually active,” she explains.

Delany-Moretlwe, who works at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, says that the injection is “discreet and convenient and not visible” and therefore “overcomes barriers” for many women in African countries.

The HPTN 084 trial involved 3,223 cisgender women ranging in age from 18 to 45. Only four women who received the injection acquired HIV compared to 34 women who took the pill.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a result like this for HIV prevention in women,” says Delany-Moretlwe. “This is a product that can be used by men and women, when it’s licensed, potentially, so I think that’s what’s exciting.”

“I’ve worked in HIV prevention for a long time and I know we’ve had more disappointments than successes,” Delany-Moretlwe says, but “it’s an incredibly exciting result. With introduction and use of the injection, we can hopefully begin to see the reduction and possibly elimination of HIV acquisition in young women in our region.” Amelia Tait

Bristol: the people behind Britain’s greenest big city

Clean and serene: Corn Street in the heart of Bristol. Photograph: Sam Frost/The Guardian

Imagine a city where power is generated from turbines and waterways. Where cycle paths, green space, allotments, veg boxes and vegan restaurants are plentiful, buses are powered by human waste and streets are closed so kids can play. It’s not a fantasy. It’s happening today in Bristol, a city increasingly feted for pioneering environmentally friendly urban life.

The first city in the world to declare a climate emergency and Britain’s first European Green Capital, it is consistently top of various green matrices. This year it was judged the most environmentally friendly big British city based on high recycling rates (47.4%), generous green space (29 hectares), council seats held by the Green party (11) and carbon emissions and gas consumption.

A green virtuous circle appears to be whirling in the West Country, as environmentally conscious citizens urge their leaders to make more ambitious climate commitments. In 2014, Britain’s first “poo bus” was launched, its journeys between Bristol and Bath entirely powered by human and food waste.

Bristol’s leaders have looked further ahead than most. Back in 2007, the city began powering its 34,000 street lights with green electricity and, by 2014/15, it had reduced its emissions by 38% compared with 2005. The Bristol Energy Co-operative’s most exciting new scheme proposes using the water flowing through Netham weir in the city to generate electricity.

A community team working at the Lawrence Weston housing estate gained planning permission for the tallest turbine of its kind in England, which will power all 3,500 homes in the area. Other schemes include a phone app using thermal imaging to help 70% of residents who struggle to pay their electricity bills identify the energy efficiency of their homes. Traders then fix problems for an affordable fee. Mark Pepper, project development manager of Ambition Lawrence Weston, says “from being seen as a middle-class problem” paying attention to the climate crisis is now seen as a way of investing in the future.

As well as being a middle-class concern, environmental issues have typically been championed by people who are overwhelmingly white. This, too, is changing in Bristol, the first major city in Europe to elect a black mayor, Marvin Rees.

“Someone said, ‘I hear the voice, I hear what the voice says but I don’t hear my voice’,” says Carlton Romaine, coordinator of the Black and Green Ambassadors project in Bristol, which aims to create a new generation of environmental leaders from black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. “We want to empower the BAME community because we’re always at the bottom and we’re usually add-ons,” says Romaine. “We want to be leading green projects or at least a partner, not just somebody that is asked to do something.” Patrick Barkham

Vodka made out of thin air: toasting the planet’s good health

The Air Company, based in New York, makes vodka from two ingredients: carbon dioxide and water. Each bottle that’s produced takes carbon dioxide out of the air. It has been chosen as one of the finalists in the $20m NRG COSIA Carbon XPRIZE, which aims to incentivise innovation in the field of carbon capture, utilisation and storage.

The company’s chief technology officer, Stafford Sheehan, hit upon the idea while trying to create artificial photosynthesis as a chemistry PhD student at Yale. Photosynthesis, you may remember from chemistry at school, is the process by which plants use sunlight to convert CO2 into energy. For 2bn years, plants were equal to the task of balancing the carbon in the atmosphere – but now we are emitting it at a rate beyond what nature can restore with photosynthesis. Hence the interest in carbon capture. “Our aim is to take CO2 that would otherwise be emitted into the atmosphere and transform it into things that are better for the planet,” says Sheehan

A nice cold martini is undoubtedly better for the planet than global warming. Unfortunately, however, it would require 11 quadrillion Air Vodka Martinis to make any kind of significant impact. But Sheehan hopes to make alcohol for a variety of different applications. “Ethanol, methanol and propanol are three of the most-produced chemicals in the world, all alcohols,” he says. “Plastics, resins, fragrances, cleaners, sanitisers, bio-jet fuel… almost all start from alcohol. If we can make the base alcohol for all of those from carbon that would otherwise be emitted, that would make a major impact.”

Air Company currently captures its CO2 from old-fashioned alcohol production: concentrated CO2 rising from a standard fuel-alcohol fermentation stack is transformed into vodka. That’s a fairly boutique product. However, power stations are much more plentiful sources. “You can burn natural gas, then capture the CO2 you’re emitting, and that feeds you the carbon dioxide,” says Sheehan. “That’s what we’d like to do and that’s where you can do it at scale.” Richard Godwin

Boyan Slat, founder of Ocean Cleanup, wears sunglasses made from reclaimed plastic waste

Cleaning up the ocean: ‘Things that seem insoluble can be solved’

The Pacific Trash Vortex is the largest accumulation of rubbish in the world. Ocean currents mean the Eastern Garbage Patch near Japan is locked in a perpetual exchange of tyres, toothbrushes, discarded Minion toys, etc, with the Western Garbage Patch, between California and Hawaii. It spans more than 1m sq miles. Most of it is plastic: an estimated 87,000 metric tonnes broken down into 1.8tn tiny pieces.

In 2012, a Dutch teenager named Boyan Slat gave a Ted Talk that had grown out of a school project. He revealed a plan to install a series of floating platforms that would harness those ocean currents and concentrate the rubbish in tighter areas, making it easier to remove. He founded the company Ocean Cleanup in 2013 and raised over $40m in funding.

“There isn’t an instruction manual for doing this,” says Slat when I connect with him over video link – no longer a wide-eyed kid but a shaggy haired 25-year-old.

After much research and trial and error, the company is now concentrating most of its efforts on rivers, stopping at source most of the plastic before it can get into the oceans. However, Ocean Cleanup achieved a significant milestone last year by extracting plastic from the ocean and turning it into something useful: sunglasses, yours for $199.

The frames only represent a drop in the ocean in terms of plastic extracted, but Slat hopes they will create a virtuous circle. Each pair will fund the clean-up of up to 24 football fields of plastic from the Garbage Patch. “It would be quite poetic if we could fund the clean-up by recycling the plastic we take out.”

Slat sees 2021 as an inflection point – the moment to deliver on its promises. “We have the tools to do it now. We have applied the lessons we’ve learned. Now it comes to actually doing it at scale.”

What gives him hope? “The willingness of the world to address the issue. When we started, I thought the main difficulty would be people not caring – and the technology would be relatively easy. Actually it’s the opposite. But that makes me hopeful that when all the tools are there, it will actually happen. It is possible, even in this time when everything seems so polarised, to tackle problems through all the things humans are good at: entrepreneurship, ingenuity, creativity. It can bring people together. Things that seem insoluble can be solved.” Richard Godwin

Saved from extinction: the rare species back from the brink

A good year for kakapos: Sinbad, a male kakapo, curiously peering from the bushes during the day. Photograph: Nature Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

Antarctic blue whales Blue whales were abundant off South Georgia before industrial whaling arrived in 1904. By the 1970s they had vanished from the surrounding seas. Between 1998 and 2018 there was only a single sighting. This year, that changed: there have been 58 blue whale sightings.

Kakapo The kakapo is the world’s heaviest, longest-lived parrot – a flightless, nocturnal creature which, like New Zealand’s other flightless birds, was imperilled by the mammalian predators introduced by humans. Years of conservation efforts had saved it from extinction, but then the species was struck down by the respiratory disease aspergillosis. Stricken birds were helicoptered to Auckland and treated in a human hospital with a paediatric nebuliser. The virus was contained and the population now stands at 213.

Beavers It seemed like 2020 was the year every grand estate obtained a licence to release beavers into large, fenced enclosures. The beaver is increasingly valued as a natural flood-defence engineer, with its dams storing water upstream and slowing the flow of flood water, protecting towns downstream. Its ponds and channels have also been shown to benefit fish, amphibians, insects and birds. This year, the government in England allowed beavers unofficially released in the River Otter in Devon to stay, paving the way for its return as a natural native species, 400 years after being hunted to extinction.

Great fox spider The critically endangered spider was feared to be extinct in Britain. But the nocturnal 5cm arachnid, known for its speed, agility and ambush hunting, has been rediscovered on a Ministry of Defence site in Surrey. Mike Waite from Surrey Wildlife Trust rediscovered the spider after being allowed in to survey the area over a two-year period. MoD sites are often wildlife havens with land undisturbed by the general public.

Hen harrier A fine spring and summer across the UK meant that voles bred prolifically in the wild, in turn helping birds of prey enjoy successful breeding years. The endangered hen harrier enjoyed its best breeding year for nearly two decades. Nineteen nests produced 60 chicks. Patrick Barkham

The future of farming? The Mayhew’s dairy farm. Photograph: Phil Fisk/The Observer

Regenerative farming: a return to nature-friendly agriculture

Four years ago, Rebecca Mayhew lost her job, then the pigs on the farm she owned with her husband Stuart were plagued by health problems due to the way they were intensively farmed. The couple became uneasy about the animals’ welfare and the health of their conventionally farmed land, so they sold their pigs and took a holiday in Scotland, where Rebecca fell in love with a friend’s Jersey cows.

Four years on, their once-conventional arable and pig farm is a very different beast. The Mayhews have embraced regenerative farming, a way of working that aims to fix the food production system by restoring degraded soils and reducing and ultimately eliminating artificial fertilisers and pesticides.

The revolution at the Mayhews’ 500-acre South Norfolk farm began with a small herd of Jersey cows. Unlike a traditional dairy, where calves are removed from their mothers after a few hours and fed formula, they chose to produce milk naturally, allowing calves to feed from their mothers, who are milked just once a day. “Looking into what’s good for the cows, and what’s good for us led us into looking at what’s good for the land,” says Rebecca.

The Mayhews have jettisoned the farming orthodoxies of the past half-century. Ploughing is sacrilege: it erodes fertile top-soil. Decades of relentless scaling-up is turned on its head: big fields are turned into smaller fields – hedges replanted to stop erosion and provide shade and fodder for the cattle. Grazing fields that would normally be sown with a monoculture of rye-grass are instead seeded with up to 20 species to provide healthier food for the cattle (which, in turn, need fewer expensive veterinary drugs). Arable fields are planted with “cover crops”: so clovers are planted alongside barley or oats. Clovers are “nitrogen-fixing” plants that take nitrogen from the atmosphere and add it to soil, so it can be used by other plants – a free fertiliser and soil-improver.

“Modern conventional farming is a constant war with nature. It’s about killing everything so one plant can grow,” says Mayhew. “We need to mimic nature and work with it.”

The Mayhews’ new way of farming is nature-friendly so they’ve been able to take advantage of government subsidies for wildlife-enhancing farming. British farmers know that generous EU farm subsidies are coming to an end and farm payments in the future are likely to be more dependent on farms providing environmental “goods” such as healthy soils and clean water. Patrick Barkham

A new way of seeing: live video signals are sent to the brain’s visual cortex. Photograph: Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

Bringing sight to the blind: developing a new artificial eye

Between the ages of 42 and 57, Bernardeta Gómez from Spain couldn’t see a thing. But then scientists embedded a port into her skull and after 16 years of blindness, Gómez was able to see again. It was all thanks to the innovations of Eduardo Fernandez, director of neuroengineering at the University of Miguel Hernández in Elche, Spain.

Fernandez is working on a unique cure for blindness – instead of developing an artificial retina, he has created a device that restores sight by feeding signals directly to the brain. As the majority of blind people have damage to the nerve system connecting the retina and the brain, Fernandez’s work could help more people than developing an artificial eye.

Fernandez has compared his prosthesis to a pacemaker or cochlear implants, both of which are pieces of electronic equipment that have been widely implanted into humans for more than 60 years. His system is made of a small camera attached to a pair of slightly outsized black glasses. This relays live video to a computer, which translates the footage into electronic signals. These signals are sent through a cable to a 100-electrode implant in the brain’s visual cortex (hence the port in the back of Gómez’s head), which deliver currents directly to the brain, producing sight.

Among the many novel terms that have entered our lives lately – “lockdown,” “herd immunity,” “flatten the curve” – one is decidedly more glamorous. In November it was suggested that “Dollying” should become shorthand for referencing an occasion when a celebrity does something that makes you love them even more.

This was in response to the revelation that Dolly Parton had contributed $1m towards the Moderna Covid vaccine, news which was met with euphoria as we collectively – and only slightly melodramatically – exclaimed that Dolly had “saved the world”.

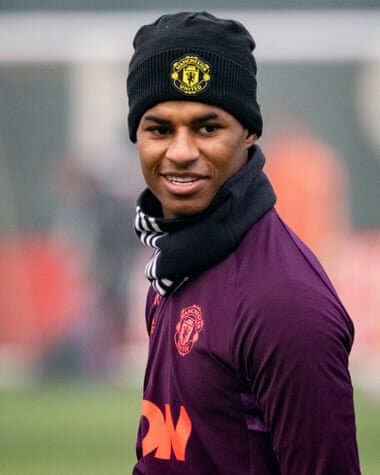

Yet before we add “Dollying” to the dictionary, let’s consider the competition. How about “Doing a Rashford”, in reference to Man Utd’s striker Marcus Rashford forcing the UK government to confront child poverty and reinstate free meals for underprivileged schoolchildren?

Gómez was able to see a low-resolution representation of objects rendered by white-yellow dots and shapes. She could see lights, letters and shapes at 10 pixels by 10 pixels. Although she couldn’t make out human faces, she was able to play a simple computer game “piped directly into her brain”. Unfortunately, the implant had to be removed after a year. “The body’s immune system starts to break down the electrodes and surround them with scar tissue,” explains Fernandez, “which eventually weakens the signal.”

He hopes to continue testing his bionic eye while figuring out ways to stop the implant degrading. Ultimately, the prosthesis will be wireless. Amelia Tait

Doing a Rashford: a new shorthand for celebrity philanthropy, in light of the footballer’s campaigning against child poverty. Photograph: Ash Donelon/Getty Images

Celebrity philanthropy: when the great are also really good

“Riri-ing” could also work, following Rihanna’s donation of $2m to charities supporting domestic-violence victims during lockdown. And then there’s “Pitting” (I sense this cute word game has now run its course), after Brad Pitt was spotted delivering groceries to disadvantaged LA households. The internet squealed with delight.

These acts stand out in a year in which celebrities have been stripped of red carpets and live concerts and rendered impotent, left to spout platitudes over social media.

Philanthropy has become common ever since Bob Geldof’s Live Aid concerts for famine-stricken Ethiopia in the 1980s, and is now so widespread it’s “almost part of the job description of an A-list star,” says Jo Littler, sociology professor at London’s City University. It is, she adds, “a form of brand promotion”.

This means we have an ingrained scepticism when we see a celebrity doing a good thing: is it genuine or a PR play? Evan Ross Katz, a fashion writer and podcast host, says acts resonate when, instead of “affixing themselves to something because it’s trendy,” the celeb has a personal connection to the cause. Such was the case with Rashford, who subsisted on free school meals growing up, or ASAP Rocky, who last month delivered meals to the homeless shelter in New York where he and his mum sought refuge when he was young.

Gestures needn’t be grand. Ryan Reynolds recently sent 300 parkas to a school in the remote Inuit community of Arctic Bay after the town’s mayor tweeted that they were desperate for winter gear. Justin Timberlake bought a wheelchair-friendly van for a teenager with cerebral palsy. And Taylor Swift’s longstanding custom of helping out regular folks continued when she paid for an 18-year-old to study maths at a UK university.

We don’t need our celebs to be decent people but when they are – and in a way that isn’t overly forced and holier-than-thou – it provides a much-needed boost to our battered morale. Jamie Waters

Anti-ageing: the worms that may help us live longer, healthier lives

At first glance, Jarod Rollins’s work looks like magic. In a cove on an island off the coast of Maine, Rollins spends his days examining transparent worms in the hopes of extending human life. Of course, it’s not really magic, it’s science: Rollins works at the MDI Biological Laboratory, a non-profit research institution, and is motivated by a desire to “help people age more gracefully or even turn back the ageing process”. In July 2019, Rollins and 10 other researchers from across the globe made a monumental breakthrough: they increased the lifespan of some Caenorhabditis elegans worms by 500%.

The reason these unassuming roundworms are frequently used in ageing research is because they share many of their genes with humans. An ordinary C elegans worm will live for three to four weeks – Rollins and his team kept them alive for months.

“If we do make a discovery in C elegans and find a gene that helps regulate the rate at which they age, there is a good chance that that research is going to apply directly or indirectly to humans,” he explains. “I’m not in the business of making worms live longer,” he laughs, “I want to make people live longer and healthier, and worms are just one step on the way.”

The worms in the experiment lived longer because his colleagues in China altered two signalling pathways in their cells. These pathways were previously both linked to ageing – in the past, experiments altering one of the pathways had doubled C elegans’s life expectancy, while experiments with the other increased the worms’ lifespan by 30%. The team expected that altering both pathways simultaneously would see worms living 130% longer. Instead, they lived five times longer.

Mutating the two pathways sends signals to cells telling them to use dietary nutrients to go into “maintenance mode” instead of “growth mode” – fixing the damage caused by age. But what are the immediate repercussions? Rollins explains that scientists used to look for one “silver bullet” in anti-ageing research, but the therapies that “are going to have the most effect are probably going to stimulate multiple different genetic pathways at once… This is really going to change how people look at the ageing process.” Amelia Tait

Why 2020 will make us better

Troubled eras have always inspired positive human progress – and 2020 will be no different, says Peter Frankopan, professor of global history at Oxford University

This year has been a terrible and chastening experience. But rather than allow doom and despair to sweep us away, we should be optimistic about the future – and in the long run, we might just owe 2020 a debt of thanks, rather than mutter its name with spite.

The experiences of this year will – and must – teach important lessons about being better prepared for future epidemics. It will lead to greater understanding of how to plan and execute large-scale emergency responses more quickly and more efficiently and with better outcomes. And it will make us think about the risks and threats in the world around us with greater clarity and depth.

The fact that Covid-19 vaccines have been developed with astonishing speed might encourage those who fear the worst about other big problems. Climate change is the most obvious mega-threat: in the long run, our pandemic experiences must help with that.

While Covid hit the economy, one outcome may be smarter policy that looks to keep people in jobs, ensures towns and city centres remain vibrant and encourages small businesses to flourish and grow – rather than enabling virtual monopolies to impose strangleholds over the economy which heighten social inequalities.

And 2020 has forced a recalibration of ambitions and expectations on a personal level. At the start of the year, our aims might have included a promotion or a higher salary. Today, those hopes have been replaced by something rather more modest and, indeed, better for us: to see friends, visit the pub, watch live sports, go to the theatre or visit somewhere new.

Outside the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd in May proved a catalyst in raising voices who demand a fairer, more equitable and kinder society. It forced global public attention to focus on the realities of discrimination and racism, to recognise that there might be better alternatives to having statutes of rich slave-owners towering over town squares and that cultural imperialism did not end when the age of empire did.

Beyond 2020? We would do well to remember that, in the past 30 years, more people have been lifted out of poverty than ever before; more children and mothers have survived childbirth; more people are able to read and write than at any point in human history.

For all the horrors of the year, hope is still present – as the historian Agathias wrote in the sixth century, times of disaster throw up prophets who talk about doom and gloom and predict how much worse things will get with great certainty. Much better, then, to be positive and optimistic.