Alistair Bunkall,

Defence and Security correspondent

There is nowhere in Africa where the waters are rising as fast as Saint-Louis.

The colourful city on Senegal's northern border with Mauritania was once celebrated as the Venice of Africa, but the sea that surrounds it is now closing in so fast that ten metres are lost to the incoming tide each year.

Along the crumbled seawall, houses teeter at impossible angles, completely uninhabitable.

They will fall into the sea any day and then the frontline will move inland another few metres.

The waves of the southern Atlantic are drowning the old French colonial capital and taking lives with them.

More than 100 million people live along the west African coast - four million of those have been displaced, forced to live in temporary camps away from the shoreline.

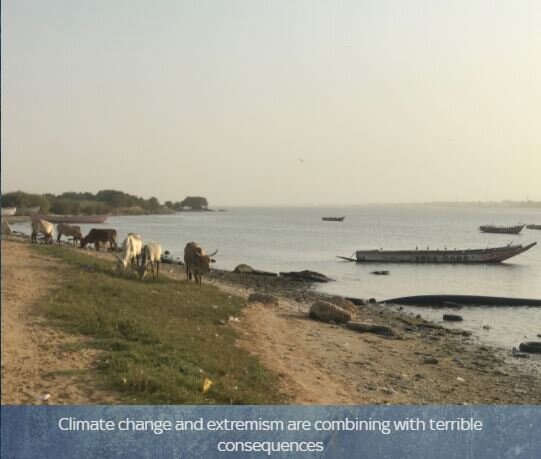

You can draw a viable line of extremism from coast to coast across the African continent and connect it to climate change.

"When droughts come and wipe out herds of cattle, that leaves people susceptible to be swayed to follow extremists who come into their communities and then pretend they can provide for them," Mohamed Chambas, the UN special representative for the Sahel, told Sky News.

"We know that is false, they cannot. They lead them to death and destruction. But this [climate change] is certainly one of the triggers, important factors to conflict in the Sahel."

Most of those countries in the Sahel region find themselves in the grip of vicious conflict as militants battle weak governments.

France has more than 5,000 troops fighting insurgents in Mali, a former colony.

They are backed up by a tiny British contingent that transport troops and equipment around in Chinook helicopters, but it's not enough.

The UN peacekeeping force in Mali is struggling to keep control. It is regularly attacked by militants and is often described as the UN's "most dangerous mission".

The death toll in the country is rising rapidly, more than 4,000 were killed in 2019.

A few hundred British soldiers were set to join the UN mission in Mali this summer, but the deployment has been delayed because of coronavirus.

They will deploy by the end of this year, all being well.

Few think it will be "peace-keeping" in the traditional sense – it could prove to be the riskiest British operation in many years.

Across the Sahel, there are small numbers of British, American and other European forces training West African militaries - but it is a slow process against an evolving enemy.

We witnessed a large multi-national exercise and saw how Nigerian, Cameroonian and Moroccan forces are learning counter-terrorism drills from their Western allies.

They are fighting an enemy that is moving freely across borders in spaces that few can still live in.

It is a war against extremism and the elements, and the truth is, they're not winning it.