Richard Partington

Fears variant will amplify shortages, driving up inflation, or even force repeat of earliest phase of pandemic

Western governments could be forced to bring in fresh emergency financial support for businesses and households if the Omicron coronavirus variant causes a severe global slowdown, a leading economic thinktank has warned.

Sounding the alarm as more cases are identified, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said a renewed wave in the pandemic threatened to add to the existing strain on the world economy from persistently high levels of inflation.

Should Omicron prove more transmissible than other variants or more resistant to existing vaccines, it could exacerbate disruption to already battered supply chains and risk driving up inflation for a prolonged period, the Paris-based organisation said.

If it takes a more severe turn, it could also force governments to impose tighter mobility restrictions, hurting demand for goods and services, and leading to a sharp fall in economic activity and lower inflation, similar to the earliest phase of the pandemic.

Laurence Boone, the chief economist of the OECD, said there were two scenarios facing the international economy as Omicron adds to the uncertainties in the recovery from the Covid-19 crisis.

“One is where it creates more supply disruptions and prolongs higher inflation for longer. And one where it is more severe and we have to use more mobility restrictions, in which case demand could decline and inflation could actually recede much faster than what we have here,” she said.

If the Omicron turned out to be “more evil” than other variants, Boone said, governments could be called upon to step in to cushion the blow for businesses and households. “That could be a scenario where we need more fiscal support at this stage,” she added.

Already in the UK, bosses of pubs, bars and restaurants are reporting a wave of cancellations for Christmas party bookings amid fears over the new variant, in an early sign of its harmful economic impact.

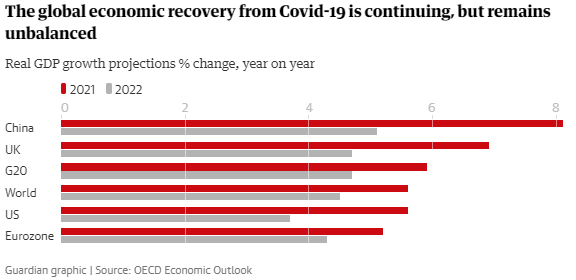

Publishing its latest economic outlook report, the OECD said the world’s recovery from previous lockdowns was continuing but that momentum had eased and was becoming increasingly imbalanced.

It added that the failure to ensure rapid and effective vaccination around the world was proving costly, with uncertainty remaining high and as new Covid variants are identified.

The outlook projects global GDP growth at 5.6% this year and 4.5% in 2022, before settling back to 3.2% in 2023, close to rates before the pandemic.

Boone said the G20 group of wealthy nations had spent about $10tn (£7.5tn) in emergency support since the start of the pandemic, but that it would take just $50bn to ensure vaccination worldwide.

“The news about the Omicron variant may actually be a reminder of how shortsighted that failure has been. We’re spending to support our economies, while we’re failing to vaccinate the whole world,” she said. “As a result the world really is not looking better.”

The intervention by the OECD comes as concern grows over persistently high levels of inflation across the world economy. While demand for goods and services has soared after the easing of lockdown measures earlier this year, supply constraints and freight bottlenecks caused by continuing pandemic disruption have led to shortages of materials, pushing up prices.

Central banks around the world are grappling with rising inflationary pressures. The chair of the US Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, signalled on Tuesday he would support a quicker withdrawal of emergency pandemic stimulus measures in response, while the Bank of England has been tipped to raise interest rates within weeks.

The OECD increased its inflation forecast for next year to 4.4%, up from the 3.9% estimated in September. It predicts largest increases in the US and the UK, with rates of 3.1% and 4.4% next year respectively.

Although warning that the new variant could lead to higher and more persistent inflation, Boone said most central banks had been waiting to see whether supply tensions would diminish, “and rightly so”.

“Faced with supply bottlenecks and where overall demand is not excessive, the best central banks can do is actually to signal that they will act if the pressure continues to increase. But it is for companies and governments to address the bottlenecks,” she added.