Damian Carrington

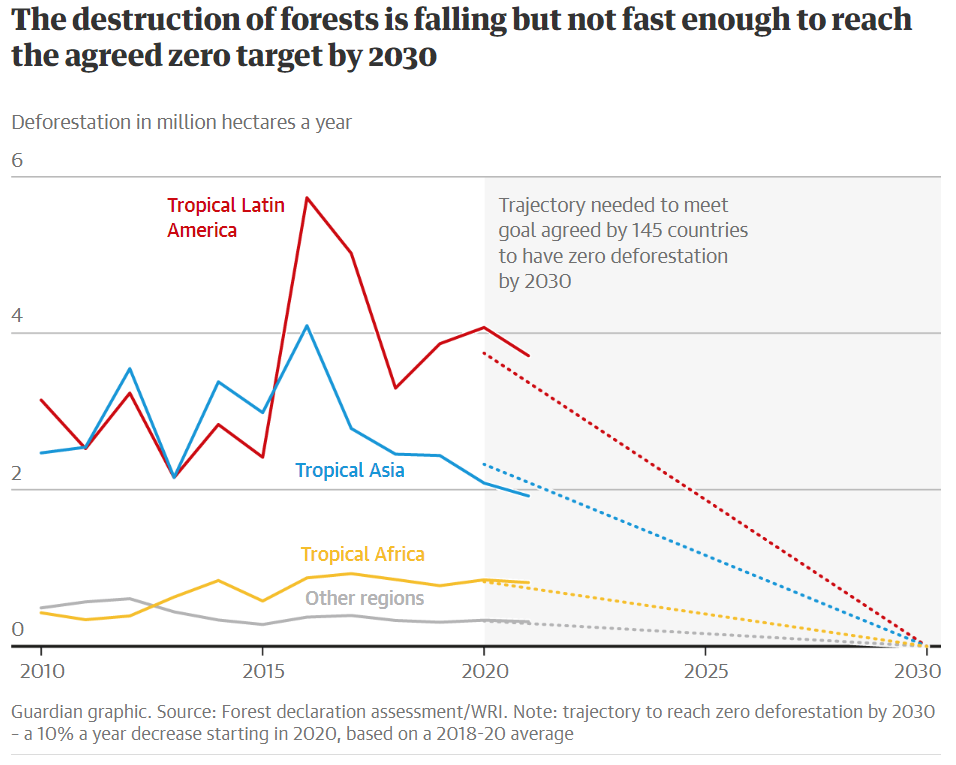

Destruction of forests slowed in 2021 but not enough to meet 2030 commitment made by 145 countries

The destruction of global forests slowed in 2021 but the vital climate goal of ending deforestation by 2030 will still be missed without urgent action, according to an assessment.

The area razed in 2021 fell by 6.3% after progress in some countries, notably Indonesia. But almost 7m hectares were lost and the destruction of the most carbon- and biodiversity-rich tropical rainforests fell by only 3%. The CO2 emissions resulting from the lost trees were equivalent to the emissions of the entire European Union plus Japan.

Aerial view of deforestation in Mato Grosso state, Brazil, in July 2021. Photograph: Amanda Perobelli/Reuters

Global heating could not be limited to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels without ending deforestation, experts said. At the UN’s Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow last year, 145 countries pledged to end the felling of forests by the end of the decade. The demolition and degradation of forests causes about 10% of global carbon emissions.

However, based on current trends, the Glasgow leaders’ declaration would be as “hollow” as the pledge made by countries in 2014 to end deforestation by 2020, the assessment’s authors said.

There was little clarity or transparency of the measures being taken to end deforestation and only 1% of the required funding was being provided, they said, and most importantly a lack of political will.

Erin Matson at Climate Focus, a policy group and one of the coalition of organisations that conducted the assessment, said: “The [Glasgow declaration] was a big moment, the first time such a target had been embraced at the leaders level by so many countries, covering 90% of global forests.

“But we are not on track. There has been some modest improvement, but even this could just be temporary. Many countries are putting their progress at risk by phasing out or rolling back protections. For example, Indonesia did not renew its palm oil moratorium after it expired in September 2021 and a recently adopted law on job creation poses a serious threat to natural forests.”

The largest area of destroyed forest in 2021 was in Brazil, where deforestation has risen under president Jair Bolsonaro, having fallen under his predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The election contest between the two men, on 30 October, has been described by scientists as likely to determine the fate of the Amazon. “The stakes are high,” Matson said.

David Gibbs, a research associate at the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Global Forest Watch, said: “We are quickly moving toward another round of hollow commitments and vanished forests.”

Fran Price, at the World Wildlife Fund, said: “There is no pathway to meeting the 1.5C target or reversing biodiversity loss without halting deforestation and conversion. It is time for bold leadership and daring solutions.”

Four of the top five countries with the largest areas of deforestation – Brazil, Bolivia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Paraguay – increased the destruction in 2021.

However, “exceptional progress” in some countries showed the 2030 goal was still possible, the authors said. Indonesia, the only country to cut deforestation in each of the past five years, and its neighbour Malaysia, reduced forest destruction by about 25% in 2021. As a result, tropical Asia is the only region on track for zero deforestation by 2030.

A drive to end the razing of forests for cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast and Ghana helped deforestation fall by 47% and 13% respectively, while new national parks and measures to fight illegal logging led to a 28% fall in Gabon. Tropical Latin America, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia and Guatemala also reported cuts in deforestation in 2021.

“We have the data and we know what interventions work – the missing element is the political will to actually undertake those actions,” said Frances Seymour at WRI.

The measures include government bans combined with effective enforcement, collaborations with the beef, soy, timber and other commodity companies whose products are most linked to deforestation, international trade measures and the strengthening of the land rights of Indigenous and other local people.

Countries backing the Glasgow declaration pledged to quadruple annual funding to tackle deforestation but no information was yet available on how these pledges would be met, the authors said.

Only a quarter of the biggest global companies in the agriculture sector have announced strong policies to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains and just 20% of these are close to meeting their commitments.

The new forest declaration assessment used data on permanent tree cover loss around the world to create a baseline from 2018-20. To get to zero deforestation by 2030 requires a fall of 10% a year, meaning the current slowing of deforestation is insufficient.

Forest cover has increased in some countries since 2000 but less than the area lost. New forests could not offset the huge carbon storage and biodiversity of existing natural forests, the authors said.

Protecting intact forests had even more climate benefits than just the CO2 stored, said Seymour, thanks to their role in producing cloud cover that cools the planet. “If we take the non-carbon processes into account, they amplify the cooling effect of ending tropical forest loss by about 50%,” she said.

Michael Wolosin, at Conservation International, said: “That 50% cooling bonus should be included by forest countries in their accounting to gain the recognition and finance they deserve for the services their forests are providing to the world.”