Agence France-Presse

There is estimated 60% chance event will develop by end of July, and 80% chance of it by end of September

Severe droughts can occur in Australia, Indonesia and parts of southern Asia during an El Niño pattern. Photograph: Outback Australia/Alamy

The chance of an El Niño weather phenomenon developing in the coming months has risen, the United Nations has said, warning that it could fuel higher global temperatures and possibly new heat records.

The UN’s World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said on Wednesday that it now estimated there was a 60% chance that El Niño would develop by the end of July, and an 80% chance it would do so by the end of September.

“This will change the weather and climate patterns worldwide,” Wilfran Moufouma Okia, the head of the WMO’s regional climate prediction services division, told reporters in Geneva.

El Niño, which is a naturally occurring climate pattern typically associated with increased heat worldwide, as well as drought in some parts of the world and heavy rains elsewhere, last occurred in 2018-19.

Since 2020 though, the world has been hit with an exceptionally long La Niña – El Niño’s cooling opposite – which ended earlier this year, giving way to the current neutral conditions.

And yet, the UN has said the last eight years were the warmest ever recorded, despite La Niña’s cooling effect stretching over nearly half that period. Without that weather phenomenon, the warming situation could have been even worse.

La Niña “acted as a temporary brake on global temperature increase”, the WMO chief, Petteri Taalas, said in a statement. Now, he said, “the world should prepare for the development of El Niño.”

The expected arrival of the warming climate pattern, he said, “will most likely lead to a new spike in global heating and increase the chance of breaking temperature records”.

At this stage, there is no indication of the strength or duration of the looming El Niño. The last one was considered very weak, but the one before that, between 2014 and 2016, was considered among the strongest ever, with dire consequences.

The WMO pointed out that 2016 was “the warmest year on record because of the “double whammy” of a very powerful El Niño event and human-induced warming from greenhouse gases”.

Since the El Niño effect on global temperatures usually plays out the year after it emerges, the impact would probably be most apparent in 2024, it said.

“We are expecting in the coming two years to have a serious increase in the global temperatures,” Okia said.

Taalas highlighted that the expected arrival of El Niño could have some positive effects, pointing out that it “might bring respite from the drought in the Horn of Africa and other La Niña-related impacts”.

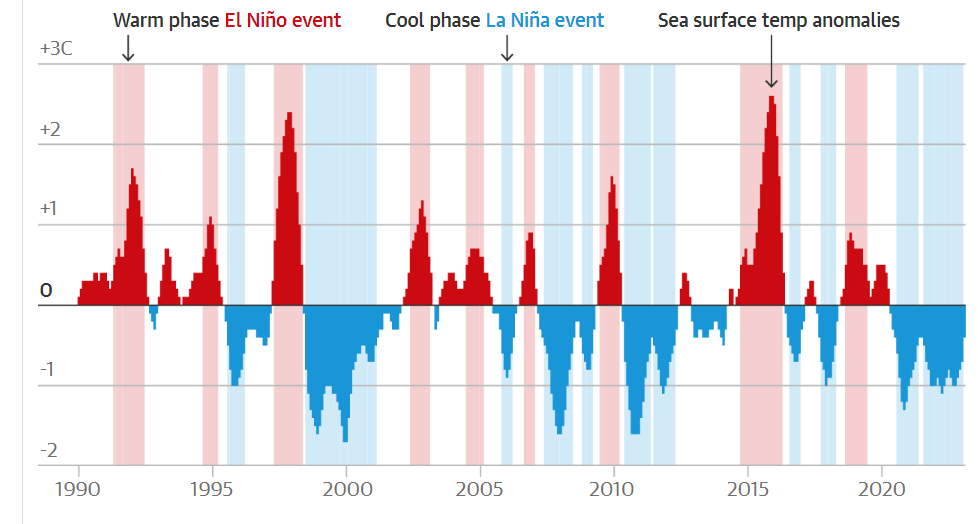

There has been a run of La Niña events in the past three years

Surface temperature anomalies and El Niño/La Niña events in the equatorial Pacific Ocean (Niño 3.4 region)

Guardian graphic. Source: Noaa. Note: an El Niño phase is five consecutive three-month running mean anomalies above the threshold of +0.5C in the Niño 3.4 region of the Pacific Ocean. The threshold for a La Niña phase is -0.5C or below. Due to warming in the region, multiple centred 30-year base periods are used

But it “could also trigger more extreme weather and climate events” he said, stressing the need for effective early warning systems “to keep people safe”.

No two El Niño events were the same and their effects depended, in part, on the time of year, WMO said, adding that it and national meteorological services would be closely monitoring developments.

The climate pattern occurs on average every two to seven years, and usually lasts nine to 12 months. It is typically associated with warming ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

Increased rainfall is usually seen in parts of southern South America, the southern United States, the Horn of Africa and central Asia, while severe droughts can occur over Australia, Indonesia and parts of southern Asia.

During summer in the northern hemisphere, El Niño’s warm water could also fuel hurricanes in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, while hindering hurricane formations in the Atlantic basin, the WMO said.