Patrick Greenfield

Author of landmark UK review into the economic value of nature joins UN environment chief in calls for ‘action, not just words’ on biodiversity goals

Plastic waste and rubbish washes up on a beach in Koh Samui, Thailand. The biodiversity goals include a pledge to protect 30% of land and sea. Photograph: Mladen Antonov/AFP/Getty Images

Humans are exploiting nature beyond its limits, the University of Cambridge economist Prof Sir Partha Dasgupta has warned, as the UN’s environment chief calls on governments to make good on a global deal for biodiversity, six months after it was agreed.

Dasgupta, the author of a landmark review into the economic importance of nature commissioned by the UK Treasury in 2021, said it was a mistake to continue basing economic policies on the postwar boom that did not account for damage to the planet.

Speaking to the Guardian six months after Cop15, where countries agreed this decade’s targets to protect nature, Dasgupta cautioned that a headline goal to protect 30% of land and sea should not lead to the destruction of the remaining 70%. He reiterated a recommendation from his 2021 report that companies must disclose the parts of their supply chain that rely on nature, so governments can take action on halting biodiversity loss.

Since the Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework was agreed in December 2022, there has been a deal to protect the high seas and first steps towards a legally binding UN treaty to regulate plastic waste. The first few months of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s presidency in Brazil has seen reductions in deforestation in the Amazon, although nature has become a culture wars issue in the EU, with proposals on restoration and pesticide reduction facing fierce opposition.

An informal update on progress towards reaching the 23 targets and four goals included in the Montreal agreement is expected to be made at Cop28 in Dubai amid continuing scientific warnings about the health of the planet.

“It is a truism: if the demand for nature’s products and services continues to exceed its ability to supply, then there is going to be a breakdown,” said Dasgupta. “It is a finite resource. We know when fisheries are depleted by continuous overfishing, it leads to the destruction of a fishery. Now try to imagine that at the scale of the biosphere.

“This excess demand [for nature] is only about 50 years old. There’s been a great acceleration in that demand since the second world war. This experience is guiding policy and it’s a real mistake because it has come at a big expense to natural capital. The decline has not been recorded in statistics. It doesn’t show up in national accounts,” he added.

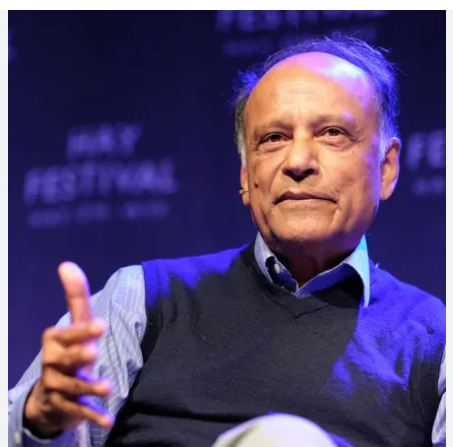

Prof Sir Partha Dasgupta talks about the economics of biodiversity at the Hay festival, UK, June 2022. Photograph: Steven May/Alamy

As an economist, I like to look at small societies as a prototype of the world economy. Studying poorer village economies tells you a lot: they are deeply dependent on natural capital. Many such societies have fallen under. We’ve seen this in Sudan with rainless areas, skinny cattle and people migrating miles and miles. It is not as if we don’t know what happens when nature breaks down.”

Among the targets and goals agreed in Montreal by all governments, except the Vatican and the US, were aims to protect 30% of the planet for nature by the end of the decade, reform $500bn (£410bn) of environmentally damaging subsidies and restore 30% of the planet’s degraded terrestrial, inland water, coastal and marine ecosystems.

Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN environment programme, said now was the time for action from governments and businesses to make the agreement reality. “We should be very proud of what was achieved. It is words on a piece of paper. We need to make them real. Everyone needs to adjust their targets and move this beyond the environment ministry to all sectors. It needs the whole of society. Action now has to be seen, not just in words,” she said.

Dasgupta’s 2021 report, inspired by the 2006 Nicholas Stern review that transformed economic understanding of climate breakdown, found the world’s economies are being put at “extreme risk” by the failure to account for the state of the natural world, and called for radical reform.

An Indigenous woman looks at dead fish near Paraopeba river in Sao Joaquim de Bicas, Brazil, after a tailings dam collapsed in January 2019. Photograph: Adriano Machado/Reuters

“I know there is a target to protect 30% of the planet in the [Cop15] deal. But the trouble with that is what happens to the other 70%. If you don’t have a policy for protecting the other 70%, you’re going to have huge pressure on it. It’s an interrelated biosphere. The 30% and the 70% are not disconnected. There are no big barriers – there’s not a Donald Trump wall between them,” he said.

As part of the Cop15 agreement, large companies around the world are required to disclose the parts of their supply chains that rely on nature and take actions to mitigate any destruction, echoing a key recommendation of the Dasgupta report.

“As citizens, we all want actions: what should the government do? What should the citizen do? What should the company do? What laws should be passed? We should insist on company disclosure of what’s happening in their supply chain. By doing so, you are sending a signal to your investors. And if they care about the fact that you’re trashing the rainforest in Brazil, they’ll punish you for it. But if they never know that you’re doing it, they won’t,” he said.