Jonathan Watts

Senior Beijing adviser also defends scale, depth and detail of country’s ‘unappreciated’ climate actions

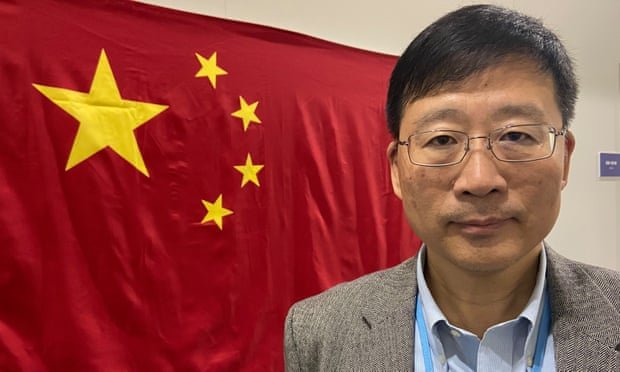

‘Unfortunately, China cannot change the China narrative,’ Wang Yi said. Photograph: Jonathan Watts/The Guardian

Chinese officials are sceptical of claims that Cop26 commitments will keep global heating below 2C, and want other countries to focus on concrete actions rather than distant targets in the final week of the talks.

They feel that China, the world’s biggest emitter, is doing more than it is given credit for, including plans to peak coal consumption by 2025 and add more new wind and solar power capacity by 2030 than the entire installed electricity system of the US.

“There has been a lot of criticism of China’s attitude in the media, but many of them are based on incomprehension or misunderstanding,” said Wang Yi, a senior adviser to the Chinese delegation.

During the first week of the UN climate talks in Glasgow, China has been portrayed at times as a reluctant laggard in the effort to keep global heating to 1.5C. The US president, Joe Biden, said it was a “big mistake” for his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, not to show up. China’s climate plan disappointed many because it contained no fresh ambition, and the country was notably absent from alliances to reduce methane emissions and phase out coal.

But Wang, a key consultant on China’s decarbonisation strategy and five-year plan, said his country had delivered a policy framework and detailed roadmap to cut emissions, while other nations were congratulating themselves on vague long-term promises.

He is sceptical of a recent estimate by the International Energy Agency and others that the pledges made in Glasgow could constrain global heating to 1.8 or 1.9C. “Based on our research, I can’t see evidence that we can reach 1.9C,” he said. “But whether we are now on course for 1.9C or 2.7C, the main point is that we should focus on concrete action.”

Wang expressed frustration that the scale, depth and details of China’s climate actions were not appreciated. “Unfortunately, China cannot change the China narrative,” he said. “To reach our targets, we have outlined a change to our entire system, not just in the energy sector but across society and the economy. Nobody knows this.”

China has released five documents detailing plans to achieve its dual goals of peaking carbon emissions in 2030 and reaching net zero by 2060. “If you read those reports you can find all of our actions, but nobody reads everything,” he said.

As an example, he said the working guidance document on carbon peaking and neutrality outlined a strict control on the increase of coal consumption during the 14th five-year period and then a gradual reduction during the following five years. “That means China will peak coal consumption around 2025, though that is not a line you will see in the document. You need to interpret it and nobody [outside China] can do that.”

Similarly, he said the government 1+N policy system provided a roadmap of 37 tasks that the country needed to take until 2060 on areas ranging from legislation and policy to technology and finance. There will be another 30 documents published in the coming year that break down actions needed in key sectors, such as building and transport, as well as major industries including steel and chemicals. “No country has issued so many documents to support its targets,” he said. “It’s a holistic solution, but nobody knows.”

China’s two different targets pose very different challenges, he said. “The peaking issue is easy. More difficult is how to achieve neutrality … We are in transition. Our concern in the future is not that China is too slow, but that it is too fast.”

He said the recent power shortages in China proved how serious it had been in shutting down overcapacity in its coal sector. Every decision had major consequences. “Our coal-fired plants have a life of 10 to 12 years. If we shut them down, who will pay for the stranded assets? Who will employ the laid-off workers?”

Decarbonisation is already under way. By the end of this decade, the government plans to reach 1200GW of wind and solar power, which would exceed the entire installed electricity capacity of the US, he said.

The final week of Cop26 will tackle the most contentious issues on the climate agenda. For China, the priority is to finalise the Paris rulebook, which will determine how money should flow across borders in support of decarbonisation, forest protection and other climate actions.

As at previous Cops, China will also push wealthy nations to make greater financial contributions to developing countries, which have done least to cause the climate crisis but suffer most from its consequences.

Wang pointed out that the 2009 promise of $100bn (£73bn) a year in climate finance had yet to be realised and far more than this would be needed in the future to accelerate the pace of decarbonisation.

“China would like more effort on supporting developing countries,” he said. “If we are going to aim for 1.5C instead of 2C, then there has to be an increase in the funds available to make that happen.”

Much remains to be done, but negotiation teams have less capacity than at previous Cops. Wang said China’s strict Covid regulations had pared down the entire delegation. “When we go back, we will have to isolate for 21 days,” he said. “So our negotiating delegations this time is just 50 people, compared with several hundred in Paris.”

He said Xi Jinping was not attending for the same reason. The fact that the Chinese president only sent a printed statement rather than a video was widely reported in the media as a snub, but Wang said this was incorrect because China had suggested a video message but the UK hosts felt it was not permitted.

China has been hesitant about pushing for a 1.5C target, which would require far more drastic actions. Wang recognised that small island nations may insist on this ambitious goal, but said it should not be to the detriment of other objectives. “1.5C is possible, but it would carry a cost, social and economic. If we cannot solve these problems equally, especially for developing countries, then it is not a real target.”

“We are all in the same boat, but different cabins,” he said. “Some live in a big space and eat too much. We need balance.”