G7 countries are responding: all of the leaders coming to Cornwall – from the US, the UK, Japan, Canada, Germany, France, Italy and the EU – have affirmed their commitment to holding temperature rises to no more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the lower limit set out in the 2015 Paris agreement.

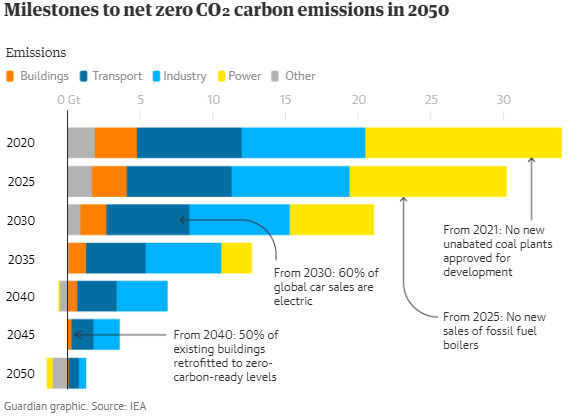

All have long-term targets to reach net zero emissions by 2050, and nearly all have targets to cut carbon in the next decade. The UK has led with a goal of cutting emissions by 68% by 2030 and 78% by 2035, based on 1990 levels. The US will halve emissions by 2030, based on 2005 levels, and the EU will make cuts of at least 55% by 2030, on a 1990 baseline.

However, current plans under the Paris agreement from Japan and Canada have been criticised by campaigners as inadequate, and they are under pressure to toughen their targets before Cop26, the crucial UN climate talks to be held in Glasgow this November.

There has been also been progress in the run-up to the Cornwall summit: all of the G7 countries have agreed to halt the funding of coal and coal-fired power overseas, a huge step forward in making a global move away from the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Yet none of this is enough. Global carbon dioxide output is forecast to jump by an almost record amount this year, as the world returns to economic growth using fossil fuels, instead of making the leap needed to renewable and low-carbon energy. G7 countries are falling behind on the “green recovery” from Covid-19 that experts have been urging for more than a year, and reliance on coal has increased in some parts of the world, including the US.

The situation is worse in non-G7 countries. China, the world’s biggest emitter and second biggest economy, is not represented at the G7, as a non-democracy and because of its status as a developing country. China’s reliance on coal has increased further in the recovery from Covid-19, despite the country’s long-term goal of net zero emissions by 2050.

Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, said that while rich countries were cutting their emissions, some developing countries would continue to increase theirs unless they could gain far more investment in shifting to a low-carbon economy.

“More than 90% of emissions in the next two decades will come from emerging economies, but they are less than 20% of global clean energy investments,” he said. “If we can’t accelerate the clean energy transition in these countries, I believe this will be the most critical faultline in global efforts to reach climate goals.”

To fund the shift to clean energy, and to cope with the effects of climate breakdown, developing countries will need help from the rich world. So far, promises of finance have not been met. Under a longstanding pledge, made in 2009, poor countries were supposed to receive $100bn a year from public and private sources by 2020. That target has been missed, and the pressure is now on the G7, the grouping of the world’s wealthiest economies, to find a way of plugging the gap – a crucial step in gaining developing countries’ backing for any climate deal at Cop26.

Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, said: “If you look at climate finance, we are far behind. Yet [given the sums the G7 are spending on coronavirus] it is pretty clear that there is enough money, and these economies are pumping money into fossil fuels.”

Stern has led a call for a doubling of climate finance from public funds in rich countries, from about $30bn in 2018 to about $60bn a year from 2025. Funding for the climate would also need to be accompanied by commitments on vaccine access for poorer countries, as leading figures have repeatedly warned that the two crises are interrelated.

Boris Johnson can hope the minor storm over his arrival by private jet will blow over quickly. More damaging is the row he leaves behind him in parliament. The government’s decision to cut overseas aid from 0.7% to 0.5% of GDP has been criticised by former prime ministers and provoked a sizeable rebellion from the prime minister’s own party.

At the G7, it has undermined the UK’s stance on climate finance and darkened any prospect of Johnson persuading other world leaders to provide the cash needed to fulfil climate finance promises. Paul Bledsoe, strategic adviser to the Progressive Policy Institute in the US, said: “It’s baffling and heartless. It’s stunning that at a moment of global crisis, as host of G7 and Cop26, the UK is the only country in the world that is reducing aid to the poorest countries.”

There are, however, still ways in which the G7 could address climate finance, he said. The International Monetary Fund is offering finance known as “special drawing rights”, that could be used to raise tens of billions for the climate emergency. Poorer countries could also be offered “debt for climate swaps” in which they would be forgiven debt in exchange for preserving forests or other carbon sinks.

“The challenge for the G7 is to think creatively about these opportunities,” he said.

What is most likely to emerge from the meeting is a fudge of warm words on climate finance, with renewed commitments to long-term goals to reach net zero emissions, and promises of action in the next crucial decade. Whatever the G7 comes up with, however, it is unlikely to measure up to the challenge.

Last month, the IEA said that if the 1.5C limit was to be maintained, all further exploration and development of new fossil fuels around the world must cease from this year, and came up with a series of milestones, such as phasing out fossil-fuelled vehicles, and fossil fuels for home heating, in the next two decades.

The G7 could make a collective commitment to embrace these policies and goals, said Morgan. “If not, it would be a complete failure of their leadership.”

When the G7 leaders fly away from Cornwall’s beaches, the last thing they may see is the writing on the sand, warning of the climate crisis. They will know that they have until November to come up with credible plans for Cop26.

“We need to see a positive dynamic for Glasgow,” said Morgan. “If not, they will go down in history as the group of leaders who had the chance of dealing with the climate emergency and who did not step up.”