What are the dangers and hazards of drinking unsafe and unclean water?

As an environmentalist with a decade of experience, researching in the Ilaje coastal region of Nigeria, I can confidently say that drinking unsafe and unclean water poses significant dangers and hazards to human health. The presence of harmful bacteria and viruses in such water can lead to various waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery and hepatitis A.

In fact, diarrheal diseases caused by unsafe water and poor sanitation are among the leading causes of death globally, with 1.6 million deaths recorded in 2017 alone. To put this into perspective, this is more than all deaths from intentional injuries combined in the same year, including suicide, homicide, conflict and terrorism. In Nigeria, about 117,000 children die annually due to poor water quality and sanitation.

Additionally, my research work has shown that exposure to contaminated water can also have adverse effects on reproductive health. Heavy metals such as lead and cadmium, which are present in high levels in the water in the Ilaje coastal region can interfere with the reproductive system.

Pregnant women who are exposed to lead may be at a higher risk of giving birth prematurely, having low-birth-weight infants and experiencing developmental delays in their children. The accumulation of heavy metals in the body can also cause chronic health problems such as kidney damage, liver damage and cancer. Urgent action is needed to address these issues and provide access to safe and clean water for communities in the region.

Therefore, it is crucial to raise awareness on the importance of clean water and sanitation and promote sustainable water management practices to ensure the availability and accessibility of safe water for all. Providing clean and safe water to communities is not only a human right but also essential to promote health, sustainable development and economic growth.

What are the various health conditions caused by waterborne diseases?

As previously mentioned, waterborne diseases significantly threaten human health and can lead to severe health complications, including dehydration, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, and even death. In Nigeria, these diseases are responsible for approximately 70 percent of all illnesses, causing over 60,000 deaths annually, with children under five being the most vulnerable due to their weaker immune systems. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that approximately 485,000 people die each year from diarrheal diseases alone, with cholera and typhoid fever also having high morbidity rates and causing severe health complications.

Additionally, consuming unsafe water can lead to other health problems such as skin rashes, eye and parasitic infections. In my research work in the Ilaje coastal region, I have observed a high prevalence of waterborne diseases and other health conditions among communities due to the consumption of unsafe water.

Providing clean and safe water to communities is crucial in reducing the burden of waterborne diseases and improving the health and wellbeing of individuals, particularly in developing countries where access to clean water and sanitation is limited. Therefore, prioritising water sanitation and hygiene interventions is crucial to ensure the availability and accessibility of safe water for all. The impact of waterborne diseases on human health and wellbeing cannot be overstated and it is our collective responsibility to take action to ensure the provision of clean water to everyone.

How does the global water crisis disproportionately affect marginalised communities and exacerbate existing inequalities?

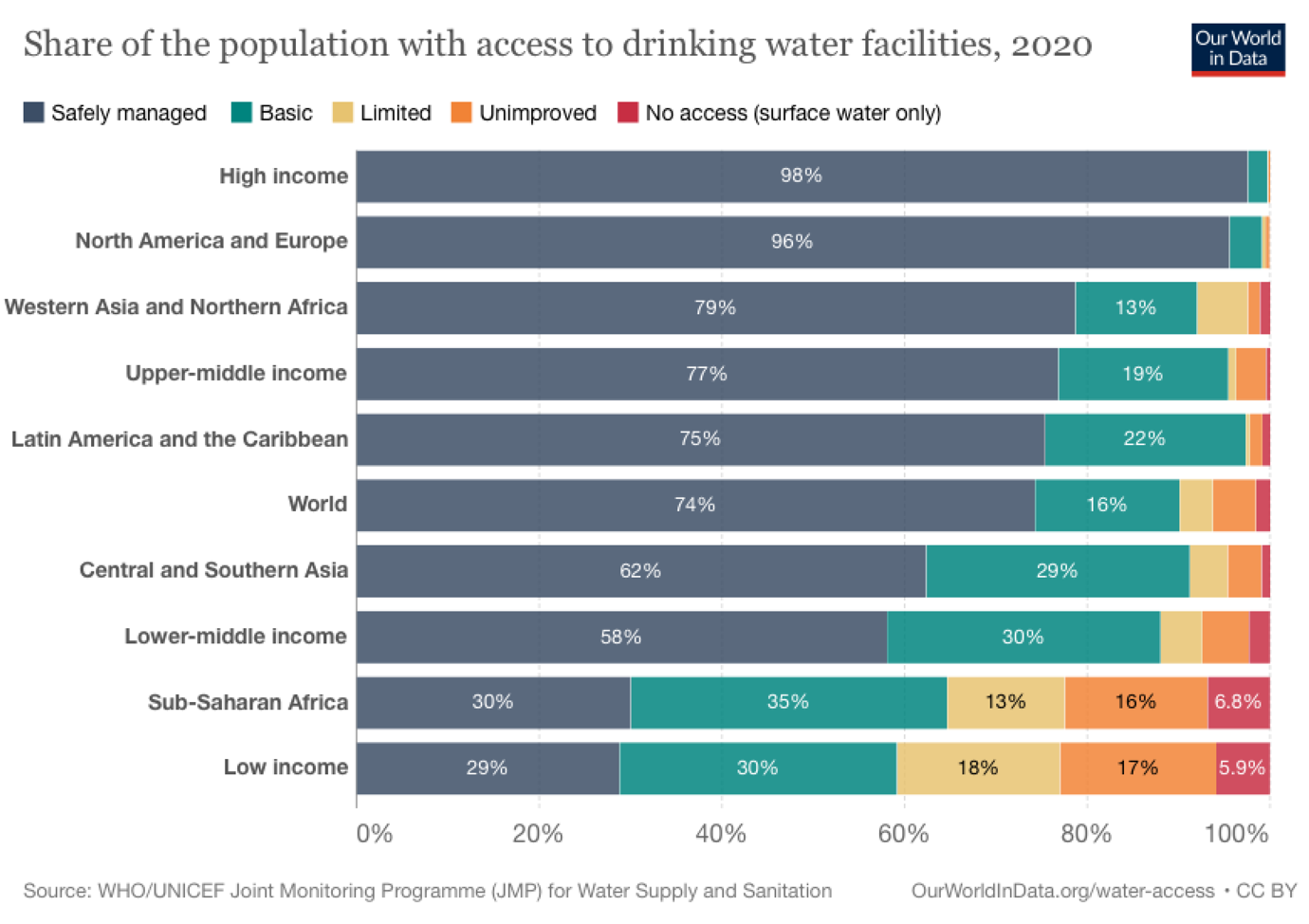

The global water crisis disproportionately affects marginalised communities and exacerbates existing inequalities in several ways. Firstly, marginalised communities such as low-income families, rural communities, and indigenous populations often lack access to clean and safe water due to inadequate infrastructure, poverty, and discrimination. According to the United Nations, approximately 2.2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, with marginalised communities being the most affected.

Secondly, the water crisis affects women and girls disproportionately, as they are often responsible for water collection in many communities. The lack of access to clean and safe water puts women and girls at risk of sexual violence and harassment during their daily water collection activities.

Thirdly, the water crisis exacerbates existing health inequalities, as marginalised communities are more vulnerable to waterborne diseases due to their limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities. This results in higher morbidity and mortality rates among these communities, leading to a further widening of health inequalities.

Finally, the water crisis also exacerbates economic inequalities, as access to clean and safe water is essential for economic development and growth. The lack of access to water can limit the potential for economic activities such as agriculture which are essential for the livelihoods of many marginalised communities.

The global water crisis has a disproportionate impact on marginalised communities, exacerbating existing inequalities in access to water, health outcomes, and economic development. It is essential to prioritize the provision of clean and safe water to these communities and address the systemic inequalities that perpetuate the water crisis.

How can we ensure that water is recognised as a fundamental human right and protected as a public good rather than have it treated as a commodity to be privatised and sold for profit?

Water is a fundamental human right essential for the survival, health and dignity of all people. Therefore, it should be recognised as such and protected as a public good. This means that access to clean and safe water should be ensured for everyone without discrimination, regardless of their ability to pay. However, the reality is that water is often treated as a commodity that can be privatised and sold for profit, which can lead to inequalities in access to water, particularly for marginalised communities.

To ensure that water is recognsed as a fundamental human right and protected as a public good, there are several steps that can be taken. First, there needs to be increased awareness and advocacy around the importance of water as a human right and the negative impacts of privatisation on access to water. This can be achieved through education and outreach campaigns, as well as advocacy efforts at the local, national, and international levels.

Second, there need to be strong legal frameworks and policies in place to protect water as a public good. These include laws and regulations that ensure that access to water is equitable, affordable and of high quality and that prevent water resources from being privatised or exploited for profit. Governments must also be held accountable for upholding these laws and policies.

Third, investment in water infrastructure and services must be increased, particularly in underserved and marginalised communities. This includes expanding access to pipe water systems, improving water treatment and sanitation facilities and increasing the availability of water storage and distribution systems.

Ensuring that water is recognised as a fundamental human right and protected as a public good requires a multi-faceted approach that includes education and awareness-raising, strong legal frameworks and policies and increased investment in water infrastructure and services. We must prioritise these efforts to ensure that everyone has access to clean and safe water, regardless of their economic status or social standing.